Imaging Review of VasculitisImaging Review of Vasculitis Franco Verde, MD; Elliot K Fishman, MD |

Disclosures None of the authors have any relevant disclosures |

Outline A. Introduction B. CHCC2012 Nomenclature C. CHCC2012 Definition and Cases D. Selected Clinical Summaries E. Clinical Approach F. Role of Imaging G. Summary |

Introduction

|

Introduction

|

Overall CHCC2012 Nomenclature CHCC categorizes non-infectious vasculitis into

|

CHCC2012 definitions and cases LVV: Takayasu (TAK) and Giant cell arteritis (GCA)

|

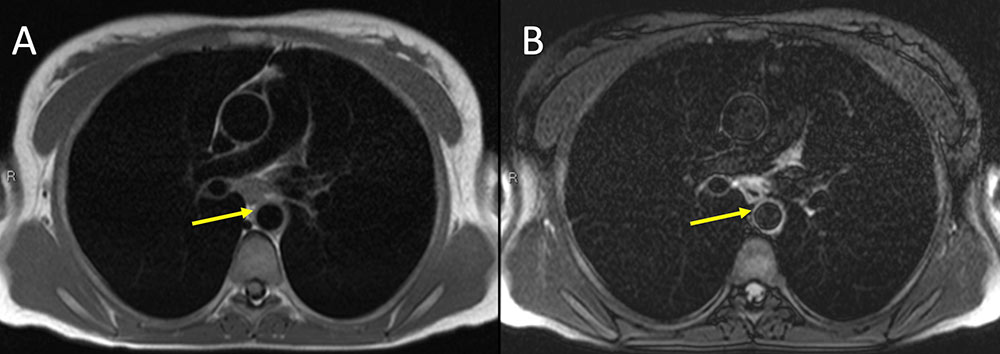

Takayasu Arteritis Figure 1. 32 year old white woman presenting with a cold arm. Non-contrast MR imaging of the chest with axial T1 darkblood (A) and axial T2 darkblood fat-suppressed sequences. Note subtle cuff of aortic wall thickening on T1 sequence (yellow arrow) with associated T2 hyperintensity. Finding raises concern for large-vessel vasculitis (Takayasu or Giant cell) or possibly medium-vessel (i.e. Kawasaki) or variable-vessel vasculitis (Bechet's) that also affects the aorta. Takayasu affects women in 80-90 percent of cases, with onset between 10-40 years. Giant-cell affects the aorta and branches but almost never occurs before 50 years old. Kawasaki disease rarely occurs in adults.  |

Giant cell Arteritis Figure 2. 68 year old woman with fatigue, mild frontal headaches, ear pain and congestion for past month. Elevated sedimentation rate of 98 with anemia. Dental exam was normal. No response to antibiotics for possible sinusitis. Eye exam was normal. Vasculitis was suspected. IV contrast enhanced CT of the chest in axial (A) and coronal (B) planes demonstrate subtle diffuse thickening of the aorta and great vessels compatible with a large vessel vasculitis. Temporal artery biopsy was positive for lymphocytic infiltrate. Findings are compatible with giant cell arteritis with this constellation of clinical findings, other negative work up, positive laboratory values, and positive temporal artery biopsy.  |

CHCC2012 definitions and cases MVV: Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) and Kawasaki disease (KD)

|

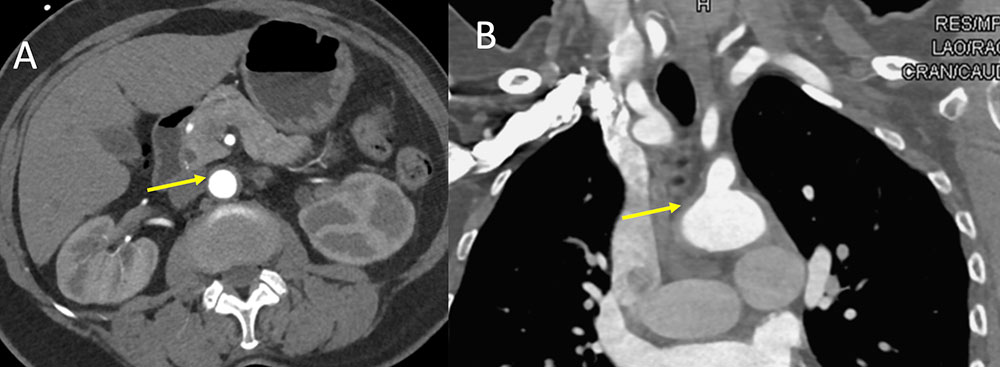

Polyarteritis nodosa Figure 3. 55 year old man with renal failure and hypertension. IV contrast enhanced CT of the abdomen with MIP reformatted images demonstrates stricturing and microaneurysm formation of multiple right hepatic artery branches (A, yellow circle and D, yellow arrow). Extensive renal artery infarcts noted (B, yellow circle and C, yellow arrow). Multi-organ involvement of medium-size vessels in a middle age man is commonly polyarteritis nodosa. The kidney is the most commonly involved organ.  |

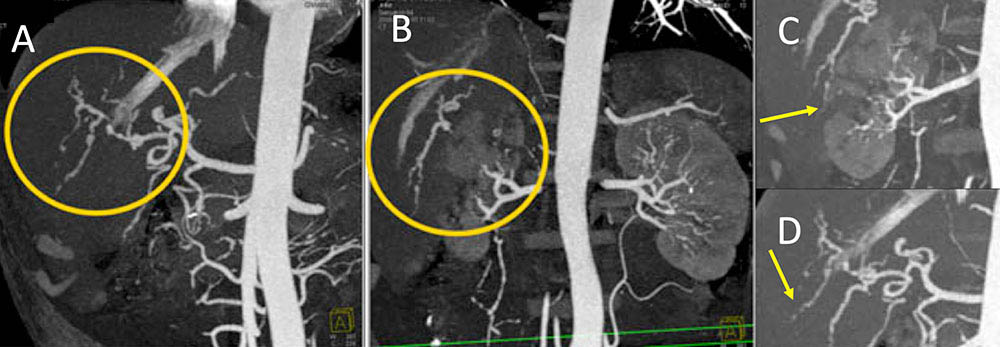

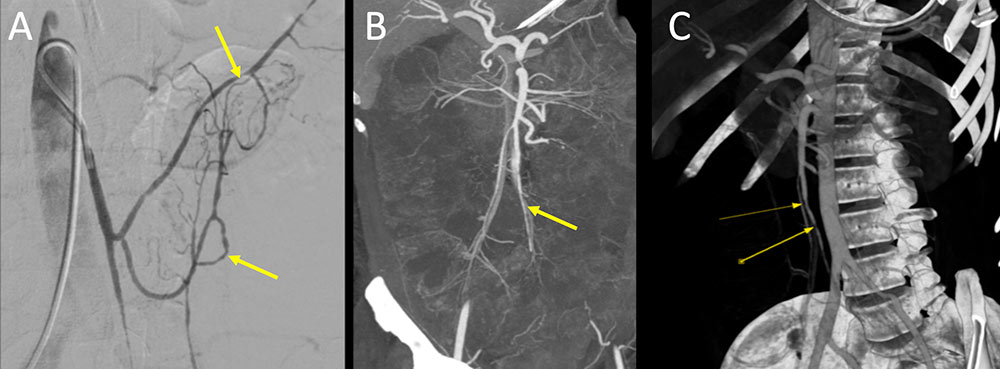

Polyarteritis nodosa Figure 4. 37 year old man with chronic medium-vessel vasculitis diagnosed 8 year prior with mononeuritis multiplex, digital ischemia status post amputations, mesenteric vasculitis, elevated RF factor, and negative ANCA. Catheter based angiogram of the superior mesenteric vessels (A) demonstrates multifocal structuring of the SMA branches (A, yellow arrows). Followup IV contrast enhanced CT performed 1 month later (B and C) demonstrates persistent multifocal narrowing of the SMA (B, C yellow arrows). Note the superior resolution of the angiogram compared to CT. Given constellation of findings, patient was diagnosed with PAN and treated with steroids and cytotoxic agents.  |

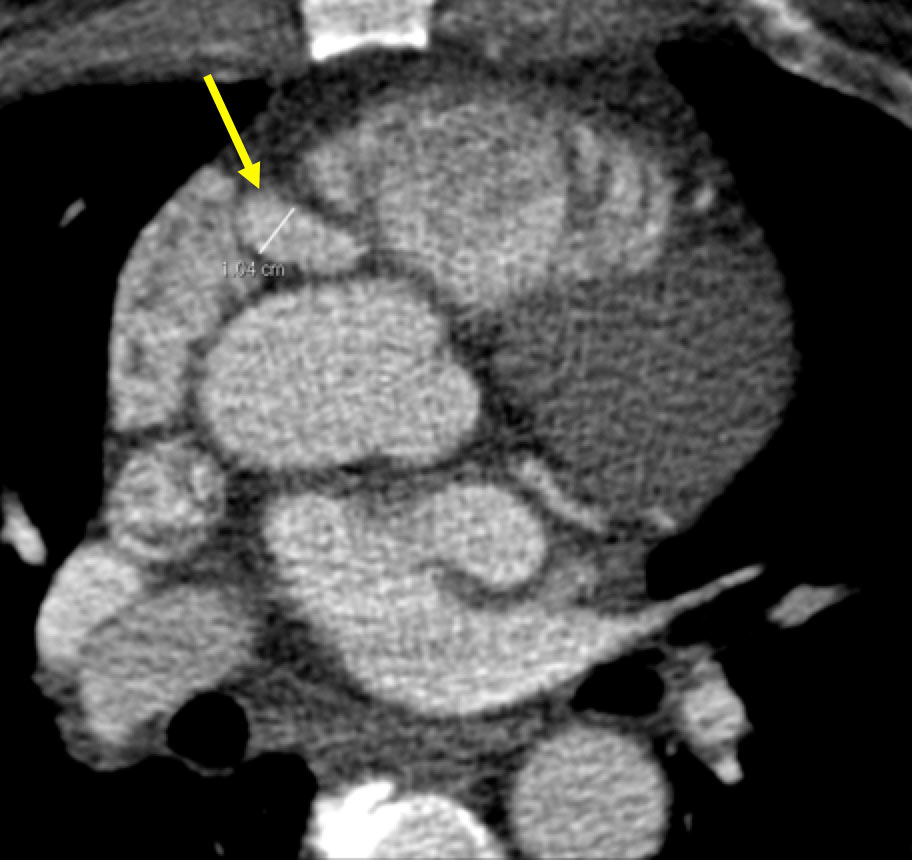

Kawasaki disease Figure 5. 53 year old man presenting with chest pain. Coronary CT angiogram demonstrates a 10 mm fusiform aneurysmal dilation of the right coronary artery. Patient has a history of Kawasaki disease as a child. Coronary aneurysms are common complications with KD. Children can present with self-limiting fever, lip and tongue erythema and swelling, rash, cervical adenopathy, hand and foot erythema. Complications include myocardial suppression causing shock, macrophage activation syndrome, cardiac valvular disease, PAD, sensorineural hearing loss, and GI abnormalities (ileus, bowel inflammation).  |

CHCC2012 definitions and cases SVV:

|

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s) (GPA) Figure 6. 20 year old man with shortness of breath and productive cough for past two days. Additional hemoptysis appearing since yesterday. Additional history reveals a 3 month history of sinusitis and epistaxis. Additional labs reveals acute renal failure, markedly elevated ESR and CRP, leukocytosis, and hematuria. ANA and cANCA were positive. No eosinophilia. Non-contrast CT in axial (A) and coronal (B) planes demonstrates extensive upper and lower lobe nodular and confluent consolidations, consistent with alveolar hemorrhage. Kidney biopsy was performed with acute necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritis. Constellation of findings is consistent with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s) (GPA).  |

CHCC2012 definitions and cases SVV:

|

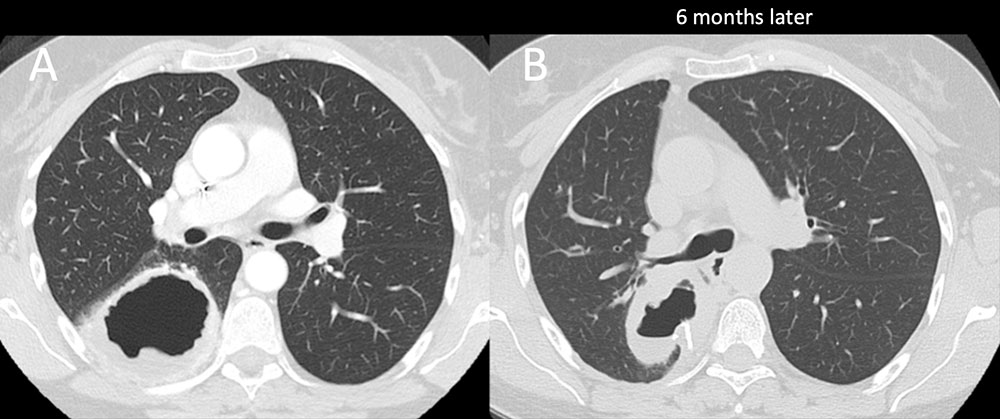

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss) (EGPA) Figure 7. 58 year old woman with history of allergies and recurrent sinusitis for the past 6 years. Patient presents with worsening cough. Initial scan demonstrates a large thick-walled cavitary mass in the superior segment of the right lower lobe. Mass was resected demonstrating a marked eosinophilic infiltration. No signs of malignancy or infection was seen. Patient returns 6 months later with a similar cavitary mass in the posterior right upper lobe. Clinical and imaging findings are compatible with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss) (EGPA).  |

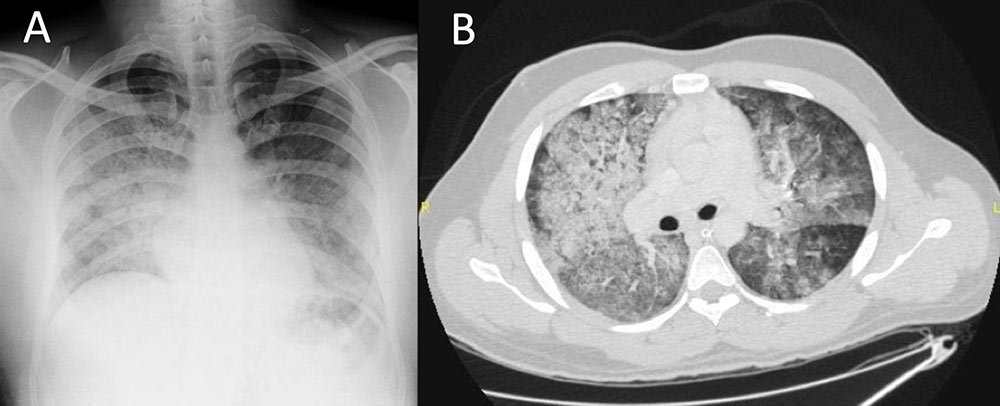

Anti–glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) disease Figure 8. 23 year old man with fever, cough, and recurrent hemoptysis for 1 month and increasing dyspnea for past week. Urinalysis demonstrated proteinuria and hematuria. Anti-GBM antibodies were present. Chest radiograph (A) demonstrates bilateral opacities, right more than left with normal heart size and no effusions. Follow-up chest CT (B) demonstrates bilateral, right more than left, consolidations with ground glass opacities. Constellation of findings are compatible with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage secondary to anti–glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) disease.  |

CHCC2012 definitions and cases SVV:

|

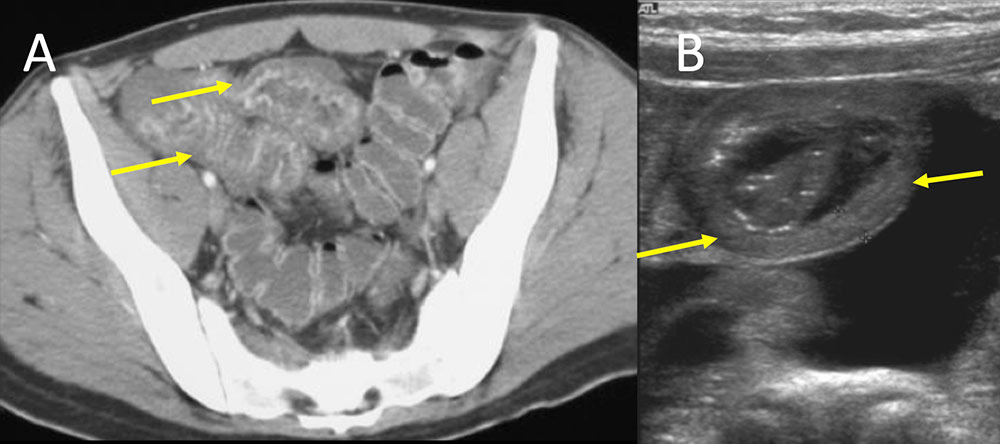

IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Schonlein) (IgAV) Figure 9. Two different patients both presenting with abdominal pain, a 20 year old man and a 5 year old girl. Patient in figure A demonstrates diffuse small bowel enhancement and wall thickening (A, yellow arrows). Second patient in figure B demonstrates circumferential small bowel edema involvemed in a small bowel intussusception on transabdominal sonogram. Both patients were diagnosed with IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Schonlein) (IgAV), which is more typical in children. Children usually present with cutaneous purpura, abdominal pain, hematuria, and joint pain.  |

CHCC2012 definitions and cases VVV: Behcet’s disease and Cogan’s syndrome

|

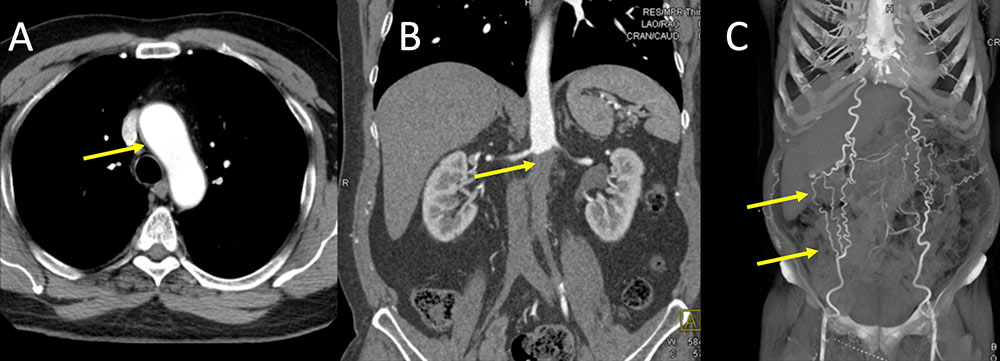

Behcet’s disease Figure 10. 54 year old middle eastern man presents for evaluation of renal mass (not shown). Patient has a long standing history of Bechet’s disease diagnosed 20 years ago. IV contrast enhanced CT images of the chest and abdomen were obtained. Subtle thickening of the aortic arch is seen (A, yellow arrow). Evidence of chronic thrombosis of the infrarenal aorta is also shown (B, yellow arrow) with well-developed body wall collaterals (C, yellow arrows).  |

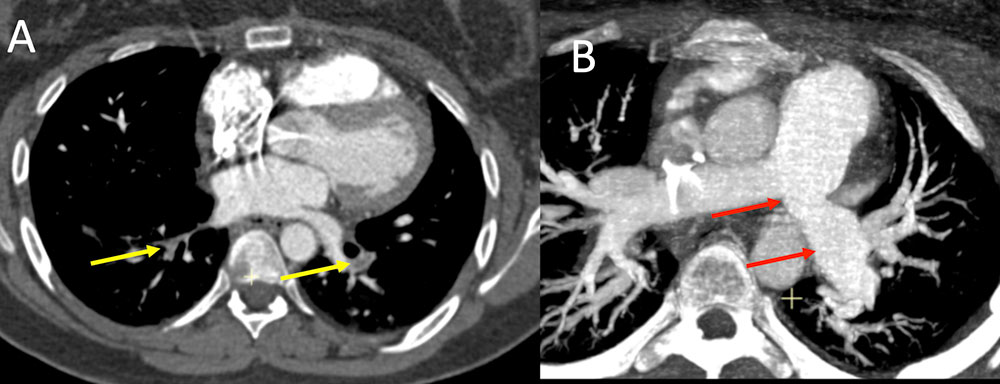

Hughes-Stovin syndrome Figure 11. 23 year old with chronic abdominal pain, chest pain, and recurrent GI bleeds, recent hospitalization for bilateral PE, currently being worked up for Behcet's, on methotrexate, s/p central line placement prior to discharge for dilaudid PCA, TPN, and antiemetics at home in the setting or oral intolerance, presents with concern for infection at site of her central line. IV contrast enhanced CT of the chest in axial (A) and axial MIP (B) images demonstrates bilateral lower lobe pulmonary emboli (A, yellow arrows) with proximal left main artery stenosis with aneurysmal dilation (B, red arrows). Patient lacked the other typical findings with Behcet’s and was diagnosed with Hughes-Stovin syndrome which is considered a forme fruste or incomplete variant of Behcet’s disease.  |

CHCC2012 definitions and cases

|

Clinical Approach

|

Clinical Approach Laboratory tests:

|

Selected Clinical Summaries Takayasu:

|

Selected Clinical Summaries Giant cell arteritis:

|

Selected Clinical Summaries Polyarteritis nodosa

|

Selected Clinical Summaries GPA and MPA

|

Selected Clinical Summaries Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

|

Role of Imaging

|

Role of Imaging Optimizing CT protocol

|

References

|

References

|

References

|

References

|