Imaging Pearls ❯ Small Bowel ❯ Perforation

|

-- OR -- |

|

- “Spontaneous gastrointestinal (GI) tract perforation is a common cause of an acute abdomen in the emergency department setting that may necessitate emergent surgery. As the surgical approach has recently trended towards laparoscopic rather than open repair, prospective identification of the site of perforation on CT imaging has become a critical part of the preoperative evaluation . It can determine the site and cause of perforation with an accuracy of 86%.”

The emergency room diagnosis of gastrointestinal tract perforation: the role of CT Borofsky S et al. Emerg Radiol. 2015 Jun;22(3):315-27 - “The normal bowel wall is thin, measuring 1–2 mm when well distended or 2–3 mm when non-distended . Thickness above 3 mm, particularly in a well-distended segment of bowel, is considered abnormal . Segmental bowel wall thickening was only retrospectively seen in 58 % of surgically proven perforations in one series. However, when seen, it led to the correct diagnosis of the site of perforation in 100 % of patients. Other series have shown segmental bowel wall thickening to be one of the most helpful signs in predicting the site of perforation, particularly in the small bowel and right colon. It should be noted that bowel wall thickening alone is a nonspecific finding that can be seen as the result of numerous entities, including inflammatory conditions, infections, and neoplasms.”

The emergency room diagnosis of gastrointestinal tract perforation: the role of CT Borofsky S et al. Emerg Radiol. 2015 Jun;22(3):315-27 - “Fat stranding is the term used to describe a hazy or reticular pattern of increased attenuation in the mesenteric fat, which is most often a sign of underlying edema related to adjacent pathology . In a retrospective review, localized fat stranding has been found to be 88 % accurate in the retrospective detection of perforation, although is only 38 % specific. Fat stranding may be of particular benefit in diagnosing a small bowel perforation, as wall discontinuity and free air are typically less apparent in this portion of the GIT.”

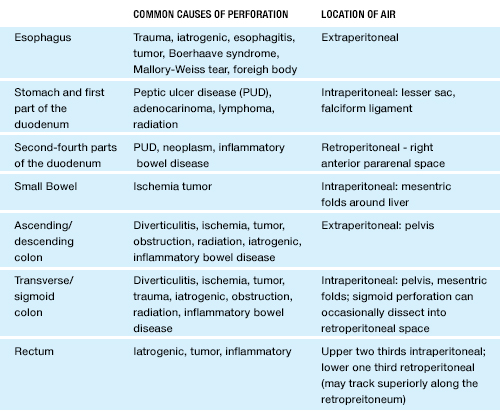

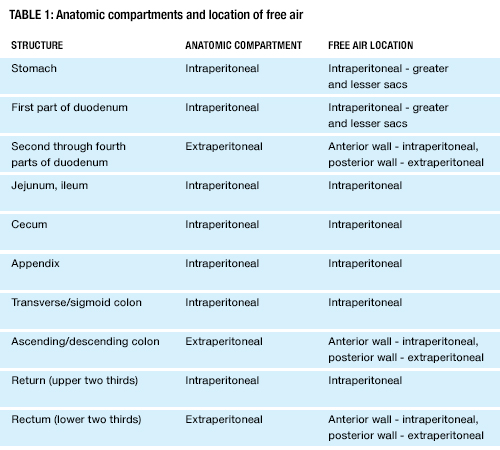

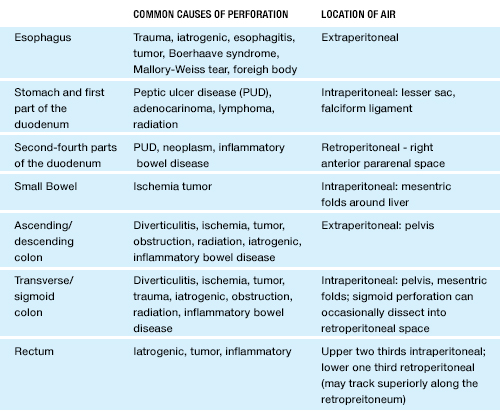

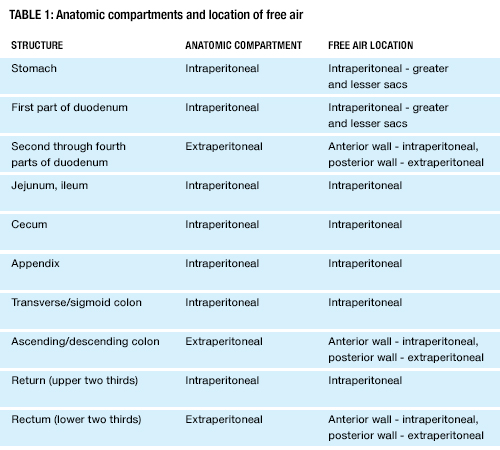

The emergency room diagnosis of gastrointestinal tract perforation: the role of CT Borofsky S et al. Emerg Radiol. 2015 Jun;22(3):315-27 - “The most frequent causes of gastric and duodenal perforations include peptic ulcer disease and ulcerated malignancies (adenocarcinoma, lymphoma). Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) usually cannot be diagnosed on CT unless the ulcer is very large or has penetrated or perforated. At times, smaller ulcers may be seen as short gas-containing areas of gastric or duodenal wall discontinuity. While the presence of free air raises specificity, it is not always seen, and the CT diagnosis relies mainly on the presence of adjacent inflammatory changes . When free air is seen, it often collects along the falciform ligament (falciform ligament sign) or in the fissure for the ligamentum teres (ligamentum teres sign).”

The emergency room diagnosis of gastrointestinal tract perforation: the role of CT Borofsky S et al. Emerg Radiol. 2015 Jun;22(3):315-27 - “Jejunal and ileal perforations are less frequently encountered than gastric and duodenal perforation but may occur secondary to Crohn’s disease, diverticulitis, and ischemia, which may be from obstruction, volvulus, or intussusception. Perforations distal to the duodenum present with a lesser amount of free air than those caused by more proximal GIT perforations. In fact, nearly half of small bowel perforations present do not present with detectable extraluminal free air. When free air secondary to a small bowel perforation is seen, it is often interposed between the leaves of the small bowel mesentery. The presence of free air deep to the abdominal wall and around the liver surface will help confirm the diagnosis. Bowel wall thickening and mesenteric stranding may be seen in association with the site of perforation. In patients with a small bowel neoplasm, free air may be caused by tumor necrosis, particularly in cases of lymphoma, which should prompt a more careful search for a small bowel mass.”

The emergency room diagnosis of gastrointestinal tract perforation: the role of CT Borofsky S et al. Emerg Radiol. 2015 Jun;22(3):315-27 - “It is important to differentiate perforated appendicitis from non-perforated appendicitis, as it can affect management. The CT findings of perforated appendicitis include extraluminal air, extraluminal appendicolith, phlegmon/abscess, and discontinuity of the appendiceal wall. Extraluminal air in close proximity to the appendix is over 98 % specific for appendicitis, while a periappendiceal abscess is 99 % specific . However, it should be noted that free air is infrequently encountered in cases of acute appendicitis. The presence of a large amount of inflammation or abscess often precludes laparotomy, which is the standard treatment for uncomplicated appendicitis.”

The emergency room diagnosis of gastrointestinal tract perforation: the role of CT Borofsky S et al. Emerg Radiol. 2015 Jun;22(3):315-27 - “Common causes of colonic perforation include diverticulitis, neoplasm, inflammatory bowel disease, and bowel ischemia. The sigmoid colon is the most common site of large bowel perforation owing to the frequency of diverticular disease in this location. Perforation of the anterior wall of the colon often results in the intraperitoneal free air. Free air from perforation of the transverse colon may be trapped within the leaves of the transverse mesocolon. Perforation of the posterior wall of the ascending and descending portions of the colon can lead to retroperitoneal air in the right and left anterior pararenal spaces, respectively.Although the accuracy of CT in predicting the site of perforation in the large bowel remains high (67–77 %), it is less predictive than localizing the site of perforation in the upper GI tract (97–98 %). Interobserver reliability has also been demonstrated to be lower with lower GIT perforations.”

The emergency room diagnosis of gastrointestinal tract perforation: the role of CT Borofsky S et al. Emerg Radiol. 2015 Jun;22(3):315-27 - “Common causes of colonic perforation include diverticulitis, neoplasm, inflammatory bowel disease, and bowel ischemia. The sigmoid colon is the most common site of large bowel perforation owing to the frequency of diverticular disease in this location. Perforation of the anterior wall of the colon often results in the intraperitoneal free air. Free air from perforation of the transverse colon may be trapped within the leaves of the transverse mesocolon. Perforation of the posterior wall of the ascending and descending portions of the colon can lead to retroperitoneal air in the right and left anterior pararenal spaces.”

The emergency room diagnosis of gastrointestinal tract perforation: the role of CT Borofsky S et al. Emerg Radiol. 2015 Jun;22(3):315-27 - “Air from barotrauma, pneumothorax, and pneumomediastinum can dissect inferiorly between the abdominal wall and peritoneum. This can be confused for free intraperitoneal air, particularly if the thorax is excluded from the scanning field. Scanning the patient in the decubitus position can solve this problem. Intraperitoneal air will move to the anti-dependent position while air trapped between the abdominal wall and peritoneum will stay in the same position. Also, scanning more cephalad may pinpoint the exact origin of the air. In the performance of a median sternotomy, the superior peritoneal cavity may be inadvertently entered resulting in pneumoperitoneum. Likewise, a malpositioned percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube can result in a similar finding.”

The emergency room diagnosis of gastrointestinal tract perforation: the role of CT Borofsky S et al. Emerg Radiol. 2015 Jun;22(3):315-27 - “Malignant pneumatosis refers to air in the bowel wall secondary to bowel wall ischemia. Clinical findings are usually apparent on physical examination. CT may not be able to distinguish between benign and malignant pneumatosis. However, familiarity with both benign and malignant etiologies of pneumatosis is important, as erroneous attribution of all cases of pneumatosis to mesenteric ischemia may lead to unnecessary surgical procedures.”

The emergency room diagnosis of gastrointestinal tract perforation: the role of CT Borofsky S et al. Emerg Radiol. 2015 Jun;22(3):315-27 - CT Signs of GI Tract Perforation

- Free intraperitoneal/extraperitoneal air

- Localized foci of extraluminal air

- Mesenteric fat stranding

- Bowel wall thickening

- Extraluminal fluid

- Extraluminal abscess

- Oral contrast extravasation

- Bowel wall discontinuity